Welcome to the American Revolution, the topic that never seems to end! Since American Independence Day is on Saturday, this seems like a perfect time to finish my history lesson. Yay history! Today, we’re ending the American Revolution. I don’t care if this post is 5,000 words; this war ends here.

Before we begin the end, you might want to refresh your historical knowledge by reading the previous parts or you could just sissy out and read the recap below:

History Lessons With Goldfish: American Revolution Part 1

History Lessons With Goldfish: American Revolution Part 2

History Lessons With Goldfish: American Revolution Part 3

History Lessons With Goldfish: American Revolution Part 4

History Lessons With Goldfish: American Revolution Part 5

Recap

We left off with America continuing to do this to the King of England, King George III:

In response, the King’s General sent 700 men against 70, and lost over 250 in the round trip journey, because Paul Revere and friends warned the rebels they were coming.

239 years ago, we declared ourselves independent, though the King didn’t see it that way and continued to wage war on the uppity colonists.

Things weren’t going all that well for the Americans with 3,000 casualties just in defending two forts (that they lost anyway) and pretty much the entire American Navy pretending they were submarines before submarines were invented, so they asked France and Spain for help. Being not too keen on the King, they agreed.

After months of retreating, George Washington crossed the Delaware on the offensive to kick some Hessian butt in New Jersey on Christmas eve, 1776.

History Lessons With Goldfish: The American Revolution

Emboldened by Hessian butt-kicking all over New Jersey, Washington won a second major victory. Yay! Then, he hunkered down for the winter. I’ve been in New Jersey in the winter; it’s not exactly balmy. At one point during the winter, he was down to only a thousand men, but by spring, his stores were resupplied to c. 9,000 soldiers.

In April of 1777, Benedict “Traitor” Arnold, beat the Brits in Connecticut and the Continental Congress returned to Philadelphia from Baltimore.

But in June, British General John Burgoyne and 7,700 soldiers invaded from Canada. Thanks a lot, Canada. Burgoyne’s plan was to meet up with General Howe in New York City to cut New England off from the rest of the colonies. Meanwhile, General Howe captured Fort Ticonderoga, whose loot Washington needed a lot.

In July, Howe and 15,000 soldiers sailed from New York to Chesapeake Bay to capture Philadelphia instead of meeting up with General Burgoyne, who had spent a miserable month crossing 23 miles of northern wilderness. Welcome to America, General Burgoyne.

Howe forced Washington’s main army of over 10,000 men to retreat again to Philadelphia, then past it, but both sides suffered heavy losses. For the second time, Congress fled Philadelphia as Howe settled in.

In September, the fleeing continued as Congress retreated yet again from Lancaster to York, Pennsylvania, which was just about the last time anything of national political importance happened in York, PA.

Finally, in October, there’s a victory! In The Battle of Saratoga, Generals Horatio Gates and Benedict “Turncoat” Arnold, defeated Gen. Burgoyne. After traipsing through the woods for a month and being soundly defeated, Burgoyne and his entire army of 5,700 men surrendered to General Gates.

The captured troops were marched to Boston, put on ships back to England and told never to return. News of this embarrassment spread like a Twitter hashtag through Europe. The French heard about it and celebrated it as if it was their war and they did it. Woooo!

In February of 1778, the French made it their war when they signed some treaties with America. America and France agreed to fight until independence was won, and more importantly, France agreed to become a major supplier of military supplies to America.

England, being jerks at this point in history, fired on some French ships. France declared war on England in 1778. England declared war on the Dutch for trading with the French and Americans, and because why not. By 1780, England was at war in the Mediterranean, Africa, India, The West Indies, America, as well as the very real threat of an invasion from France and Spain. Way to make friends, England.

Anyway, back in March 1778, after the loss at Saratoga, British Parliament sent a Peace Commission to Philadelphia to negotiate. The commission agreed to all of America’s demands except independence. Whereupon, Congress told them to get bent. Buh-bye.

In June of 1778, fearing a blockade by French ships, British General Clinton withdrew from Philadelphia and moved toward New York City. Once the coast was clear, Congress, once again, moved back to Philadelphia. I hope they got frequent flyer miles, or perhaps, frequent fleer miles.

In one of many cases of weather-related bad timing for allied American invasions (See D-Day, WWII), American ground troops and French ships ended up fighting weather instead of the British in Newport, Rhode Island. Most of the French ships had to be sent to Boston for repairs without having fought.

British and Indian forces started a major campaign in the south in December, because starting a war in New Jersey in December is silly. They captured Savannah, Georgia and Augusta a month later.

For most of the war, British allied troops–this includes, British, Indians, and American loyalists–set fire to every town they saw, including New York City, Portsmouth and Norfolk, Virginia, and for fun, they killed people, usually civilians, e.g., Cherry Valley, New York where over 40 settlers were straight-up massacred.

In June of the following year, Spain got all up in the warrin’ and declared war on England, but didn’t high five either France or America on it. “You’re on your own, dudes.”

In September 1779, John Paul Jones was fighting and losing against a British frigate until he may or may not have said, “I have not yet begun to fight!,” which actually motivated his troops to a sort of half-assed victory. He captured the frigate, but sunk his own ship in the process. Whoopsies.

That same month, John Adams was nominated to negotiate with England. “Accept our independence, King, and we’ll stop this warrin’.” “No! Never! Off with his head!” “Well, I tried.”

General Washington suffered through yet another terribly harsh winter in 1780, this time in Morristown, New Jersey, not far from where he was in the winter of 1777. Seriously, who winters in New Jersey? Results: low morale, desertion, and mutiny over back pay and rations. So, in other words, a winter funfest. Brrrr.

In May, Washington was rewarded for suffering through winter with one of the worst American defeats yet. They lost Charleston and with it, the entire southern army (5,400 soldiers), four ships and a military arsenal. The British only lost 225 men.

In July, 6,000 French soldiers arrived fashionably late to Newport, Rhode Island. They got stuck there for a year, blockaded by the British fleet.

In August, Benedict “Judas” Arnold, became commander of West Point. Unknown to the Americans, he’d been working with the British since May of 1779. His double-crossing led to General Gates being defeated in South Carolina by General Cornwallis.

In September, Americans captured a British major in civilian clothing carrying proof that Benedict “Benedict Arnold” Arnold, was a traitor and had planned to surrender West Point. Arnold heard about the major’s capture and ran like a sissy girl flailing arms to the British army where he was made a brigadier general and actually fought against American troops. TRAITOR.

October 1780: Washington’s most trusted former aide and newly-appointed American General Greene led General Cornwallis on a six-month wild goose chase through the backwoods of South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, then back to North Carolina, much like the Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote. Weee!

January 1781: British General Tarleton got his ass handed to him at Cowpens, South Carolina, which has to be a very demoralizing place to get your ass handed to you. Cowpens. Yup.

Back in North Carolina, Wile E. Coyote stand-in, General Cornwallis lost badly in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and said, “Screw the Carolinas.” After months of wild goose chase, he retreated to Wilmington and opted to conquer Virginia. He set up a base in Yorktown on the Chesapeake Bay and established communications with General Clinton’s forces in New York.

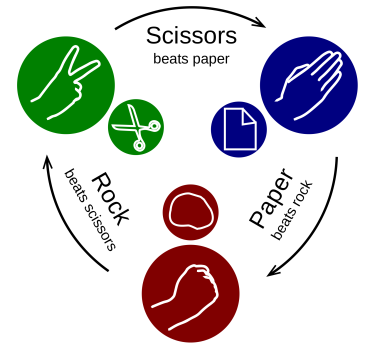

Meanwhile, Washington and French General Rochambeau met in Connecticut for a war council. Rochambeau reluctantly agreed to a joint French naval and American ground attack on New York. They may or may not have Rochambeau’d for it.

However, Washington abandoned that plan when he heard that French Admiral Count de Grasse and his 29-ship fleet was heading for Cornwallis’ little hideaway on Chesapeake Bay. Washington sent word to Rochambeau to go there instead. Damn indecisive Americans.

September 1781, Count de Grasse and his ships dumped soldiers off on land to cut off Cornwallis and then, just for fun, had a naval battle with the English navy. Outnumbered, the English retreated to New York, ostensibly for reinforcements, during which time, the French blockaded their return, and left Cornwallis high and dry.

The next month, Washington and a combined army of 17,000 attacked Cornwallis at Yorktown. French cannons bombarded the hell out of them day and night while French and American troops slowly surrounded them. Right about when Yorktown was about to be pulverized, Cornwallis surrendered to Washington, effectively ending hopes for a British victory now and forever.

The English government called for an end to the war. British Prime Minister Lord North, resigned in March 1782 and two days later, his successor, Lord Rockingham, started negotiations with the upstart Americans. On September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed, which officially ended the American Revolution, making America the land of the free and the home of the world’s largest hot dog.

THE END!

Happy Independence Day!

And remember…

Information was severely paraphrased from the following sources: